The views expressed in this Member News article are the author's own and do not necessarily represent those of Agri-TechE.

Feeding strategies to mitigate methane emissions from dairy and beef cattle pertaining to ration balancing program and use of phytochemical feed additives: A Review

a. V. Vismitha Shree, b. Parag Ghogale, c. Kumar Ranjan

eFeed Life Sciences, Research and Development,

a. Product Manager, eFeed Life Sciences

b. Senior Dairy Nutritionist, eFeed Life Sciences

c. Chief Executive Officer, eFeed Life Sciences

Abstract

The escalating global demand for animal-derived foods places strain on livestock systems, notably contributing to the 14.5% of total greenhouse gases emitted by livestock. Among these emissions, methane from cattle, primarily in beef and dairy production, stands out as a major concern. This comprehensive review explores sustainable strategies to mitigate methane emissions, focusing on early-life interventions, Total Mixed Ration (TMR) balancing, and the use of phytochemical feed additives such as essential oils, allicin, tannins, saponins, and curcuminoids. These diverse approaches not only reduce methane production but also enhance animal productivity, emphasising the critical need for environmentally responsible and economically viable practices in livestock farming.

Keywords:

Methane emissions, Livestock, Sustainable feeding, Total Mixed Ration (TMR), Phytochemical feed additives, Essential oils, Allicin, Tannins, Saponins, Curcuminoids.

Introduction

The global demand for animal-derived foods continues to rise, placing immense pressure on livestock systems. Modern feeding patterns have introduced more concentrate based rations which are leading to more emissions from dairy cattle. Livestock emissions, contributing to 14.5% of total greenhouse gases, are a major focus, with cattle being primary contributors, particularly in beef and dairy production, notably in methane emissions (1-3). Almost 71% of total methane production originates inside the rumen during digestion and fermentation of feed and forages, leading to a higher production of metabolic hydrogen (H2), subsequently converted to CH4 as a protective mechanism (3). Sustainable animal feeding is a crucial aspect of modern agriculture, emphasising the efficient utilisation of natural feed resources while safeguarding the environment and ensuring the production of economically viable and safe animal products (Makkar, 2016)

Methane emission stands as a significant obstacle to environmental sustainability, being a major contributor to greenhouse gases (Chuntrakort et al., 2014). Beyond its environmental implications, methane represents a loss of carbon sources, leading to unproductive dietary energy use, with potential losses of up to 12% of dietary energy intake (Kim et al., 2012). eFeed is currently working on strategies to reduce methanogenic microbiota in calves during the process of rumen development.

To balance conventional feed and fodder through TMR feeding to limit methanogenesis by using RationCraft software and natural ingredients to use in cattle feed or feed supplements to reduce methane emissions and thereby improve FCR of dairy animals by diverting energy lost towards production and body maintenance. Calves fed with feed additives since birth to weaning showed decrease in methane emissions post-weaning to 1 year of age. However, further research and studies are required to reduced methane emissions from calving stage as developing rumen is further going to harbour more methanogenic bacteria and archeas in due course of time.

Balanced total mixed ration and improved feeding practices results in higher feed conversion ratio, thereby increasing milk production and weight gain and also reduces methane emission. Once the protein: energy (P:E ratio) is maintained in the diet, it will help to utilise amount of protein and amino acids for growth, production and reproduction. Utilising energy in this way will allow in more hydrogen ions to be used in the process, which leads to less availability of hydrogen ions for methane generation

Research is going on various feed additives to competitively reduce hydrogen ion availability and to inhibit methanogens. Many of the ingredients are synthetic and not environment friendly. Therefore using natural ingredients will be a sustainable approach to tackle this issue.

Plant secondary metabolites, including saponins, tannins, essential oils, organo-sulphur compounds, and flavonoids, are known for their antimicrobial properties (Hague et al., 2018). Herbs and spices, rich sources of these metabolites, present a natural and safe alternative to chemical feed antibiotics (Yang et al., 2015). Feeding bioactive-endowed plant products not only benefits in sustainable management practice but also improves productivity without posing any adverse effects. This approach has the potential to mitigate enteric methane and nitrogen emissions through the modulation of rumen function and microbial community (Kamra et al., 2012; Salami et al., 2019) The inhibitory effects of oils on Gram-positive bacteria, influencing H2 production and methanogenesis, have been demonstrated in various studies (17, 18).

In conclusion, the comprehensive exploration of sustainable animal feeding encompasses bioactive feed resources, medicinal herbs, and strategic feeding. By understanding the potential of these diverse elements, researchers seek to address the dual challenge of improving animal product quality while mitigating environmental impacts, particularly methane emissions. The findings from these studies are expected to contribute valuable insights and innovative solutions to the ongoing discourse on sustainable and efficient livestock production. As global demands for animal-derived foods continue to escalate, the imperative to develop environmentally responsible and economically viable practices in the livestock sector becomes increasingly valuable.

Mechanisms governing enteric methane production

Two primary mechanisms underpin the variation in methane production in cattle. The first revolves around the amount of dietary carbohydrate fermented in the reticulorumen. This intricate mechanism involves numerous diet-animal interactions that impact the equilibrium between carbohydrate fermentation rates and passage rates. The second mechanism regulates the available hydrogen supply and subsequent methane production through the ratio of volatile fatty acids (VFA) produced.

The critical factor in this regulation is the fraction of propionic acid produced relative to acetic acid. The acetic:propionic acid ratio has a profound impact on methane production. If all carbohydrate is fermented to acetic acid with no propionic acid production, energy loss as methane would be as high as 33% (Wolin and Miller, 1988). Given that the acetic:propionic acid ratio typically varies from approximately 0.9 to 4, the corresponding methane losses exhibit significant variability.

Research indicates that as the daily feed intake of an animal increases, the percentage of dietary gross energy lost as methane decreases by an average of 1.6% per level of intake (Johnson et al., 1993b). The type of carbohydrate fermented significantly influences methane production, likely through its impact on ruminal pH and microbial population. Fermentation of cell wall fiber results in higher acetic:propionic acid ratios and, consequently, higher methane losses (Moe and Tyrrell, 1979; Beever et al., 1989). Grinding and pelleting of forages can markedly decrease methane production (Blaxter, 1989). These effects become more apparent at high intakes, with methane losses per unit of diet potentially reduced by 20 to 40%.

The addition of fats to ruminant diets influences methane losses through multiple mechanisms, including the biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids, enhanced propionic acid production, and protozoal inhibition (Czerkawski et al., 1966). While the addition of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids has been shown to decrease methanogenesis, the overall impact on total metabolic hydrogen remains relatively small. Ruminal protozoa may play a significant role in methane production, particularly when cattle are fed high-concentrate diets. Observations suggest possible interspecies hydrogen transfer between ruminal methanogens and protozoal species (Stumm et al., 1982)

Feeding strategies to control methane emissions

Feed & Fodder

Among the strategies aimed at mitigating methane emissions, dietary manipulation stands out as a straightforward and practical approach. This method not only promotes enhanced animal productivity but also contributes to the reduction of methane emissions. Dietary strategies can be categorised into two primary groups: i) enhancing forage quality and adjusting the diet proportions, and ii) supplementing the diet with additives that either directly impede methanogens or modify metabolic pathways, thereby reducing the substrate available for methanogenesis.

The prevailing method involves modifying the type or quality of forage and adjusting the concentrate-to-forage ratio in the feed. Opting for younger plants with higher fermentable carbohydrates, reduced non-digestible fiber (NDF), and a lower C:N ratio contributes to high-quality forage, ensuring increased digestibility and passage rate. This, in turn, steers rumen fermentation towards propionate production [34, 35]. As propionate serves as an alternative hydrogen (H2) sink, an elevation in propionate production results in less H2 available for methanogenesis [36]. However, solely relying on forage is insufficient to enhance animal performance, as concentrates are typically incorporated into the feed in varying proportions. Concentrates, with fewer cell walls and readily fermentable carbohydrates such as starch and sugar, play a crucial role. Studies have indicated that the addition of 35% or 60% concentrate to the feed leads to a reduction in methane (CH4) production, accompanied by improved productivity.

Essential oils and Plant extracts

Essential oils (EOs) are volatile, aromatic liquids derived from various plant sources, encompassing flowers, seeds, buds, leaves, herbs, wood, fruits, twigs, and roots [74]. Microbes exhibit varied responses to EOs, either promoting or inhibiting specific microbial groups like methanogens. Some EOs hinder protozoa growth indirectly or through biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids, limiting hydrogen availability for methanogens [77, 78]. Guyader et al. demonstrated a 29% reduction in methane emissions and a 50% decrease in protozoal population with increasing saponin dosage in an in vitro batch culture [95].

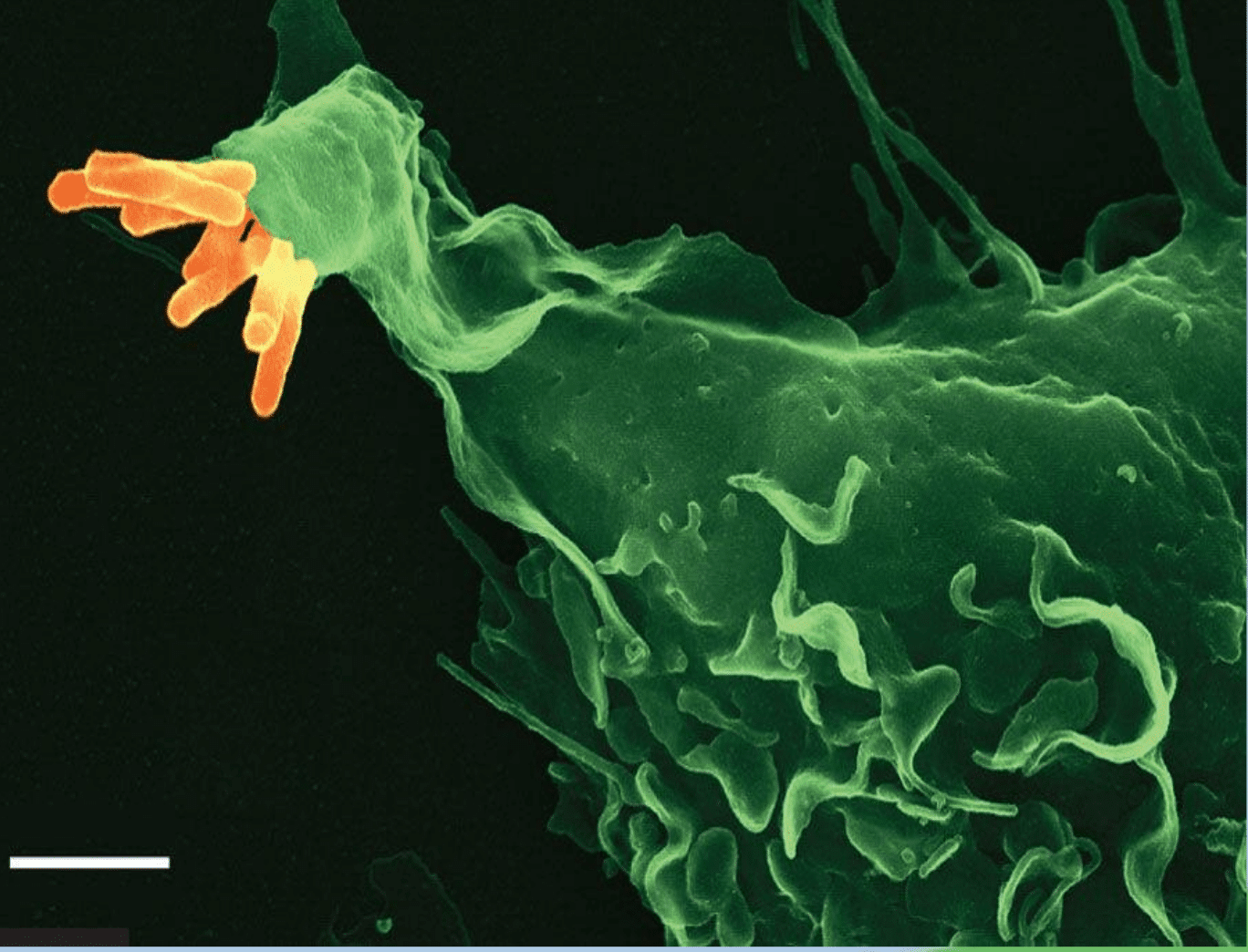

The methane-suppressing effects of plant secondary metabolites (PSM), including essential oils, are attributed to their antimicrobial properties against bacteria, protozoa, and fungi in the rumen [77, 78, 79]. Due to their lipophilic nature, essential oils have a high affinity for microbial cell membranes, impacting microbial populations by interacting with functional groups on the cell membrane [58]. Methanogenesis is further inhibited by essential oils, influencing protein degradation and amino acid determination [59]. Ongoing research is essential to explore the potential incorporation of essential oils into mainstream livestock farming practices, considering their promising impact on mitigating methane emissions and optimizing microbial balance in the rumen.

a.Cinnamon extracts

Cinnamon powder, rich in flavonoids, saponin, and tannin, has demonstrated methane-reducing properties in livestock. The addition of cinnamon powder to the substrate resulted in a notable decrease in total gas methane production, with reductions ranging between 7% and 14%. The key bioactive compounds in cinnamon, such as polyphenols and cinnamaldehyde, contribute to its inhibitory effects on methane production. Studies confirm the presence of various secondary metabolites in cinnamon, including flavonoids, tannins, saponins, and alkaloids. The tannin content in cinnamon powder, determined through the Folin Ciocalteu method, was found to be 5.64%, along with other constituents like flavonoids (7.21%) and saponins (6.02%)

b.Saponin in Yucca schidigera extracts

Yucca schidigera (YS), belonging to the Agavaceae family, holds substantial potential for various applications, historically recognized for its effective treatment of inflammatory conditions. Originally native to North America, particularly the arid Mexican desert, YS extracts (YSE) offer diverse benefits in animal nutrition. Rich in phytochemicals, including steroidal saponins and polyphenolics like resveratrol, YS is regarded as a major commercial saponin source, contributing to odour control in intensive farming. Continuous discovery of new steroidal saponins in YS adds to its bioactive profile.

Studies primarily focused on ruminants, especially cattle and sheep, reveal promising effects of YSE on gas mitigation. Increased YSE feeding in lactating dairy cows demonstrated a significant linear effect on 4-hour and 24-hour gas production. Similarly, in vitro experiments with various ruminal substrates showed increased total gas production as dietary saponin levels rose. YSE addition effectively reduced methane production in multiple studies without adversely affecting gas production rates. Adjusting saponin levels in YSE treatments aimed to avoid potential side effects on ruminal fermentation, maintaining non-significant differences in methane production. Notably, a 1% sarsaponin concentration effectively inhibited methane in steers without compromising animal performance. Ongoing analysis of YS structures and bioactive components promises further insights, offering potential applications for environmental pollution mitigation in the livestock industry and improved feed efficiency.#

c. Allicin

Allicin has been reported to reduce the production of CH4 by reducing the number of methanogens (Kongmun et al., 2011). Busquet et al. (2005) reported that CH4 production was significantly reduced by allicin supplementation. They also found that the supplementation of allicin reduced the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of methanogens. Meanwhile, Liu et al. (2013) suggested that illite had a high CH4 adsorption capacity, which reduced CH4 production in the intestine and Biswas et al. (2018) found that CH4 production was reduced by 13% with 1% illite supplementations. As a result, it was presumed that allicin affected the methanogens, reduced CH4 production and thereby increased the concentration of CO2. Based on batch culture and dual flow continuous culture studies, the supplementation of garlic oil (300 mg/L) and allicin (a sulphur-containing bioactive compound in garlic; 300 mg/L) decreased CH4 yield (mL/g dry matter (DM)) by 73.6 and 19.5%, respectively, compared with control basal diets consisting of 50:50 forage:concentrate ratio, over 24 h [37]. Dietary supplementation of allicin at 2 g/d for 42 d decreased CH4 yield (mL/g DM) by 6% compared to a control diet in sheep [10

Garlic contains the organosulphur compounds allicin (C6H10S2O), alliin (C6H11NO3S), diallyl sulphide (C6H10S), diallyl disulphide (C6H10S2), and allyl mercaptan (C3H6S) [137–140] (Figure 3). These compounds are widely known for their unique therapeutic properties and health benefits, as they act as antioxidants to scavenge free radicals [141]. Garlic derived organosulphur compounds demonstrate different biochemical pathways that may provoke multiple inhibitions [142]. One potential pathway for the direct inhibition of methanogenesis by garlic is via the inhibition of CH4-producing microorganisms such as archaea [142]. Archaea possess unique glycerol-containing membrane lipids linked to long-chain isoprenoid alcohols, which are essential for cell membrane stability. The synthesis of isoprenoid units in methanogenic archaea is catalysed by the enzyme hydroxyl methyl glutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase. Garlic oil is a potent inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase Gebhardt and Beck [142]; as a result, the synthesis of isoprenoid units is inhibited, the membrane becomes unstable, and cells die.

d. Plant polyphenols

Early studies on the effects of dietary PP focused mostly on the effect of tannins on ruminants’ performance and feed utilization efficiency: in fact, tannins have been shown to possess both detrimental and favorable effects, depending on the diet composition, the animal species, the tannin source, and the level of their inclusion in the diet (Frutos et al., 2004; Waghorn, 2008). Tannins might have a toxic effect on some rumen microbes, by altering the permeability of membranes (Frutos et al., 2004). Moreover, tannins may inhibit the enzyme activity of ruminal microorganisms (Jones et al., 1994). However, the toxic effect is strongly dependent on the dose and the nature of tannins as well as the bacteria species. For instance, an in vitro study demonstrated that the activity of proanthocyanidin against Clostridium aminophilum, B. fibrisolvens, and Clostridium proteoclasticum depended to their chemical structure, whereas the growth of Ruminococcus albus and Peptostreptococcus anaerobius was strongly affected, regardless of the fraction of proanthocyanidin adopted or the dose applied (Sivakumaran et al., 2004). Condensed tannins have a direct inhibitory effect on hemicellulases, endoglucanase, and proteolytic enzymes of several rumen microbes such as F. succinogenes, B. fibrisolvens, Ruminobacter amylophilus, and S. bovis (Jones et al., 1994; Bhat et al., 1998). Conversely, P. ruminicola is able to counteract the negative effect of tannins by producing protective extracellular material (Jones et al., 1994).

I.Tannins

An interesting development in CH4 mitigation research is the development of forages with higher levels of tannins, such as clover and other legumes, including trefoil, vetch, sulla and chicory [29]. The anti-methanogenic activity of tannins has recently been investigated in vitro and in vivo [83]. The CH4-suppressing mechanism of tannins has not been described clearly; however, this mechanism may inhibit ruminal microorganisms [77]. Tannins may inhibit, through bactericidal or bacteriostatic activities, the growth or activity of rumen methanogens and protozoa [84]. Methane production was reduced (up to 55%) when ruminants were fed tannin-rich forages, such as lucerne, sulla, red clover, chicory and lotus [81]. Although tannins appear promising for CH4 mitigation, these impede forage digestibility and animal productivity when fed at a higher concentration, limiting their future wide-scale use in CH4 abatement [19]. However, more research may identify the balance between CH4 reduction and possible anti-nutritional side effects as associated with tannin supplementation.

II. Saponins

Saponins are naturally occurring surface-active glycosides that are found in a wide variety of cultivated and wild plant species that reduce CH4 production in the rumen [29, 79]. Saponins have a potent antiprotozoal activity by forming complex sterols in protozoan cell membranes [83] and, to some extent, exhibit bacteriolytic activity in the rumen [66]. Saponins are antiprotozoal at lower concentrations [85], whereas higher concentrations can suppress methanogens [77]. Saponins inhibit ruminal bacterial and fungal species [79] and limit the H2 availability for methanogenesis in the rumen, thereby reducing CH4 production [77]. Methane reduction of up to 50% has been reported with the addition of saponins [86]. However, a wider range of CH4 reduction (14–96% depending on the plant and the solvent that was used for extraction has been reported [62].

e. Curcuminoids

Turmeric, recognized for its medicinal properties, contains fat-soluble polyphenolic pigments known as curcuminoids, contributing to its status as a medicinal plant. Enriched with nonnutritive phytochemical constituents, turmeric is acknowledged for its disease preventive properties, containing approximately 3-6% phenolic compounds collectively referred to as curcuminoids (Niranjan and Prakash, 2008).

In experiments, turmeric consistently and significantly reduced gas production when included at levels above 5 mg/g of substrate throughout a 48-hour incubation period. Notably, at 10–15 mg/g inclusion, turmeric exhibited a significant reduction in methane, carbon dioxide, ammonia, total volatile fatty acids production, and substrate degradation. Concurrently, the inclusion of turmeric led to a reduction in rumen bacteria and protozoa at 10–15 mg/g, with fungi reduction observed at 15 mg/g inclusion. Microbial biomass reduction was evident at 15 mg/g of turmeric inclusion.

Turmeric’s impact on gas production, particularly the sustained reduction above 5 mg/g, suggests its potential to inhibit carbohydrate degradation in the rumen. The initial reduction effect diminishing at 5 mg/g after 27 hours implies microbial adaptation to turmeric at lower inclusion levels during fermentation. The observed decrease in total volatile fatty acids aligns with reduced acetic acid and butyrate production, given that gas production typically occurs during the fermentation of substrate carbohydrates to acetate and butyrate. Furthermore, turmeric’s inhibitory effect on ammonia production suggests potential benefits in optimizing dietary protein utilization in the rumen, showcasing its multifaceted impact on ruminal fermentation dynamics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, addressing methane emissions from cattle is imperative for environmental sustainability. Designing diets that reduce methane emissions while maintaining optimal nutrition and productivity can be challenging. Research and development are needed to identify and refine additives that are both practical for on-farm use and environmentally sustainable. Many farmers may not be aware of or understand the importance of methane mitigation strategies. Implementing effective educational programs to disseminate knowledge and encourage the adoption of sustainable practices among farmers is challenging. Developing standardized and cost-effective measurement techniques to monitor emissions on a large scale is essential and still needs research. Methane emissions from cattle are a global issue that requires international collaboration. Coordinating efforts and policies across countries to address methane mitigation uniformly and effectively is of great importance. This comprehensive review highlights importance of mitigating methane emissions early life stage of cattle, diverse feeding strategies through TMR balancing and using advanced software , emphasising use of phytochemical additives, essential oils, and naturally occurring compounds like allicin, tannins, saponins, and curcuminoids. These approaches offer multifaceted benefits, from inhibiting methanogenesis to improving animal productivity. Phytochemical feed additives are emerging as a particularly impactful candidate, consistently reducing gas production and methane while influencing microbial populations in the rumen. The ongoing pursuit of sustainable animal feeding practices is essential for meeting global food demands while mitigating environmental challenges.

Institutional Review Board Statement: This study neither involved human/animal participation, experiment, nor human data/tissues.

Data Availability Statement: All data generated during the study are included in the published article(s) cited within the text and acknowledged in the reference section.

Acknowledgments: Open Access Funding by eFeed Life Sciences

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

References

LIC UK Ltd

LIC UK Ltd

Agri-TechE

Agri-TechE

Agri-TechE

Agri-TechE

Lombard Asset Finance

Lombard Asset Finance

Agri-TechE

Agri-TechE