Testing the air across Norfolk for a year

Technology captures fragments of airborne DNA to reveal the sometimes invisible biodiversity around us

Researchers at the Earlham Institute in Norwich have begun a year-long project of sampling and sequencing the air at sites across Norfolk.

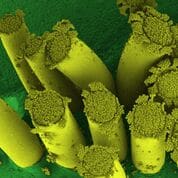

The cutting-edge approach they have developed in collaboration with the Natural History Museum, London, sucks thousands of litres of air through a filter, trapping any biological material floating nearby. This is then prepared, sequenced, and analysed to identify the species present.

The bulk of the DNA captured on the first day of sampling came from plants, likely reflecting the high pollen count in springtime.

Over the course of the next 12 months, the work will reveal new insights about the hidden biodiversity around us, differences between habitats, and how this changes with the seasons.

All living organisms continually, and unwittingly, shed fragments of their DNA into the surrounding environment. Even tiny traces of environmental DNA – sometimes called eDNA – can be detected in the air.

Researchers at the Earlham Institute are capturing and studying airborne eDNA from different environments to learn more about the biodiversity we can’t normally see.

Dr Richard Leggett, who has been leading the technology development underpinning this project at the Earlham Institute, said: “There are extremely small amounts of biological material in the air for us to sample. We have to pull in a lot of air – thousands of litres – to be confident we’ll have captured any traces of the organisms that might be in a particular habitat.

“The cutting-edge technology we’re using, alongside new techniques we’ve developed, allows us to quickly find and sequence any DNA that was in the air – which could originate from plants, animals, bacteria, viruses, or even allergens.”

One of the research group’s interests is crop pathogens, many of which use the wind to spread. These pathogens can be devastating for farmers, who can’t usually detect them until visible signs of infection appear on the plants – at which point it is often too late to save them.

Dr Darren Heavens, a postdoctoral scientist in the Leggett Group, said: “The approach we’ve developed can be used by farmers to alert them to the appearance of pathogens, allowing them to take immediate action to minimise crop losses.

“It potentially provides an unbiased, ‘always on’ monitoring system to continuously read the DNA and RNA sequences of microbes collected from the air. And, because we’re looking at the genome, we can even identify resistance genes or new strains emerging.”

The latest project sees the technology being deployed across Norfolk’s diverse habitats, with the process repeated every three months to reveal any seasonal trends. Encompassing the county’s coastline, forests, broads, and urban areas, the project will catalogue the species detected across eight sites.

On the first day of sampling, the group identified DNA from plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi from all of the sites they visited. The majority of the biological material came from plants, reflecting a season in which the air is carrying large amounts of tree pollen.

The group also detected many airborne plant pathogens, including yellow rust – a serious crop pathogen – detected at a wheat field.

Each of the sampling sites has produced a distinct profile, which will now be tracked over the next 12 months to better understand the impact of the changing seasons.

“We’re blessed to be based in a county with such an exceptionally diverse range of habitats and species,” added Dr Leggett. “This gives us a fairly unique opportunity to use the air to explore biodiversity across different environments and seasons – all without leaving Norfolk.

“We’ve got a fair idea of some of the species we might expect to find and, at this time of year, it’s no surprise to find a lot of pollen in the air. But we may pick up things we can’t identify, or that have never been recorded in the region before.

“I’m not suggesting we’ll capture evidence of a Loch Ness monster on the Broads but this is one of the best approaches for finding traces of species we’d normally struggle to spot by eye.”

A key innovation in the approach came from needing to identify the wildly different species whose eDNA had been captured.

Mia Berelson, a PhD student in the Leggett Group, explained: “When we normally sequence the genome of an organism, we collect some cells from it and extract the DNA. There’s only one individual so we know all the bits of DNA will belong to that one species.

“With the eDNA we’re collecting from the air, there will be fragments from many different species. It’s like being given one or two jigsaw pieces from lots of different puzzles, and then trying to complete all of them at the same time.”

To deal with this challenge, the group developed MARTi – a piece of open-access software specifically designed to analyse mixed samples. As the fragments of DNA are read, MARTi compares the sequence to online reference libraries.

“MARTi is a piece of extremely clever software that logs and analyses what we find, before sorting through all these fragments to tell us the different species they belong to,” explains Dr Leggett.

Dr Matt Clark, Natural History Museum, London, said: “It was fantastic to have been involved in the launch of this project, which will see the sequencing of eDNA be used to unlock rich data about the biodiversity of Norfolk’s unique habitats and a key agricultural region feeding the UK.

“When we previously worked together to trial similar technology in the old urban gardens surrounding the Natural History Museum during 2020-21, before we updated these areas, we were blown away by how the air-biome changes hugely across the seasons as indeed the ecosystem does.

“Earlham Institute’s project is building further on the technology and will show how impactful the study of airborne eDNA can be.”

The project has been enabled by funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), part of UKRI, through its support of the Earlham Institute’s Decoding Biodiversity strategic research programme.

Earlham Institute

Earlham Institute