New sequenced genome sheds light on weed resistance

Genomic advances reveal how similar weeds can dominate wheat fields that are geographically separated by over 5,000 miles.

Two new Alopecurus genomes have been sequenced, providing important additions to the growing body of community resources for weed genomics.

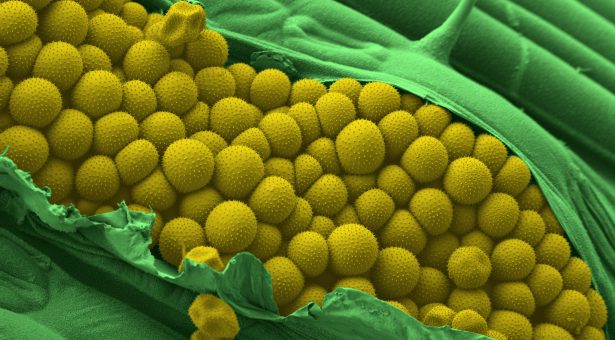

Access to the genomes for blackgrass and orange foxtail, sometimes called shortawn foxtail, will help researchers address what makes these weeds such exceptional survivors in modern agricultural systems.

The sequencing of the orange foxtail genome, which was carried out at the Earlham Institute, generated 11.7 million PacBio HiFi reads – nearly 230 Gb of data – corresponding to a haploid genome coverage of 32.9x.

Both blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides) and orange foxtail (Alopecurus aequalis) are native to many regions across the Northern Hemisphere.

Blackgrass has become the predominant agricultural weed in Western European winter wheat and barley, whereas orange foxtail has emerged as the dominant agricultural weed for similar crops in parts of China and Japan.

Both are grass weeds that grow in grass crops. They frequently out-compete cereal crops.

Changes in cropping practices have not been effective in controlling the weeds, and both have evolved resistance to multiple herbicides.

With both weeds presenting a major threat to crop yields and food security, a better understanding of the genetic drivers of their resistances and resiliencies are essential to generate effective strategies for control. Filling this knowledge gap requires high-quality genomic resources.

n December 2023, an annotated blackgrass genome was published by Rothamsted, Clemson University, and Bayer scientists. The blackgrass seeds were from a population collected in 2017 from the Broadbalk long-term experiment that had never been treated with herbicides and so remained susceptible to chemical control.

Comparing this population with resistant populations from other UK fields enabled these researchers to identify genetic mechanisms correlated with resistance.

Now, one year later, an annotated orange foxtail genome has been published. For this genome, Rothamsted researchers collaborated with partners at the Earlham Institute and the European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA) initiative, which ultimately aims to provide reference genomes for all European species.

The orange foxtail plants sequenced were from seeds held by Kew’s Millennium Seed Bank from a UK-collected population.

As orange foxtail is not present in the UK’s agroecosystem, it is unlikely they have ever been exposed to herbicides.

As with the Broadbalk seeds, this genome is an important reference as it will not have been influenced by the strong selective pressures that have shaped some weed populations.

The orange foxtail genome at 2.83 Gb is smaller than the blackgrass genome (3.572 Gb) and contained just over 33,750 protein-coding genes. The genome is assembled into a total of seven chromosome-level scaffolds, and most are complete with telomere sequences on one or both ends.

The sequencing, assembly, and analysis of the orange foxtail grass were carried out by teams in both the Earlham Institute’s Faculty and its National Bioscience Research Infrastructure in Transformative Genomics, both supported by BBSRC.

Read the full article here

Earlham Institute

Earlham Institute